What is Environmental Storytelling?

And how does it enhance a story?

No, I’m not talking about the Erin Brokovich movie and the Hinkley groundwater contamination incident. Not that kind of environmental storytelling. I’m talking about the subtle cues within locations where stories take place.

Environmental storytelling consists of small and deliberate details in the background that enhance the audience’s story experience. They create an illusion of a bigger world, imply backstory without bogging down the narrative, and can energize the fan community.

Let’s talk about the principles first and then examine them in action with a case study.

How Does Environmental Storytelling Improve a Story?

If you’re making something like a video game, the answer is a little more obvious. A player can go all over the map, the camera moves with the character, and in the case of open-world games, the story isn’t always even linear. Therefore, the developers have to tell parts of the story using only the environment.

If you’re making an animated movie, though, that doesn’t mean you should ignore the environment.

It Creates the Illusion of a Bigger World

Despite our grandiose desires to model every aspect of a world down to the loose change in the junk drawer that never gets opened, you know in your heart of hearts that work won’t get seen and won’t help the story. The Director makes the camera framing choices, and that’s it.

This gives filmmakers and animators a limitation compared to game designers, but also an advantage. While people can play and replay a game like Red Dead Redemption II for hundreds of hours finding all kinds of side adventures, you can’t do that with a linear movie. The movie’s camera choices don’t change.

But limitations aren’t bad. It turns out, you don’t have to model and animate every item in every drawer. Take this shot for example:

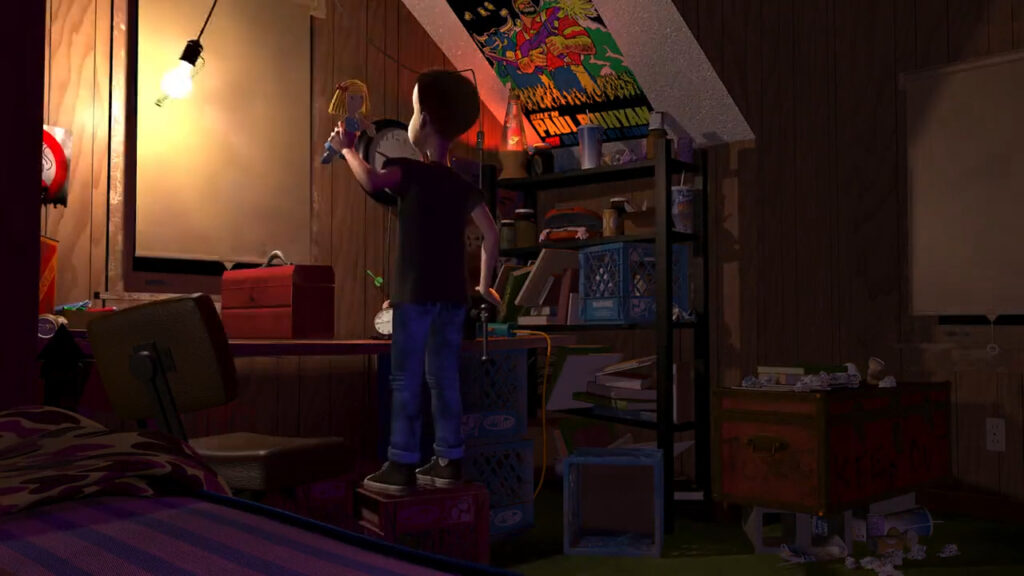

There’s a whole world outside. Other houses on the street, desk drawers full of items, handwritten scribbles in his notebooks. We know that for Andy all those things are there, but I bet you a dollar there isn’t a single polygon to render inside that tacklebox on the bookshelf.

It Implies Backstory Without Bogging Down the Narrative

Andy’s mom just told him anything that he doesn’t specifically save before he leaves for college will get thrown away.

We don’t have all day to tell the story of the years between Toy Story 2 and now that led up to this moment. Even if we did, no one would want to listen to it. You can tell all the backstory you need with a more economical manner with that small bit of dialogue and this quiet shot of him spinning around in his chair.

As he surveys the room, we see the story of his life as he grows up. Posters he hung while a child still adorn the walls, but newer posters partially obscure them. We only get a few seconds to take it all in, but that’s all we needed. A mix of two lives, child and teenager, occupy this room.

It Energizes the Fan Community

Besides the utilitarian purposes, there’s a more whimsical reason to craft deliberate environments: easter eggs.

Easter eggs will fly right past people who aren’t in the know. But to the true fans? They make the movie more endearing. Someone has gone to the effort to leave a tiny nod to something that only the truest admirer would appreciate. It gets them excited about the story.

Fans love easter eggs. Especially Pixar fans. And Pixar happily obliges the eagle-eyed viewer with easter eggs from past projects. Sometimes, there’s an easter egg for future projects that people don’t catch until rewatching an old movie later.

I bet you didn’t even notice the Finn McMissile from Cars 2 (2011) poster on Andy’s wall the first time around, did you?

What Departments are Responsible for Environmental Storytelling?

Although the Director guides the project’s creative vision, he doesn’t (and can’t) handle every element on his own.

No one person carries all the responsibility for the environment, so let’s break down a few people with key roles.

Writing

It all starts with a script. But the writers don’t specify every aspect and detail. That’s a good way to make everyone who reads the script throw it in the trash. We could have written something like this:

INT. ANDY'S ROOM - DAY

Woody climbs up on top of the dresser. He surveys the room.

It is a messy room, a mix of the young Andy and older Andy.

His walls are covered in posters. There are so many now

that they don't all fit neatly, and older ones are now

covered with newer ones. His desk is messy and has papers,

textbooks, and music CDs strewn about. On his floor lies a

duffel bag he hasn't unpacked. It's stuffed in the corner

alongside a pile of dirty laundry and several milk crates

that overflow with assorted papers. Beneath his windowsill

rests an old TOYBOX in the shape and style of a wagon from

the Woody's Round Up cartoon. Within it, he has stored all

of his remaining toys from his childhood as we knew him in

the first Toy Story movie.

That was painful for me to even write, but thank you for bearing with me through it.

Less is more. As a writer, convey what the script reader needs to know and nothing more. Compare my verbose monstrosity to how the finished script described the room:

ON THE DRESSER

Woody climbs up, surveys the room -- posters, guitar,

textbooks. He turns to a cork board where Andy’s high

school graduation photo is pinned. He lifts it to find...

A SNAPSHOT shows an eight-year-old Andy wearing a cowboy

hat and posing with Woody and Buzz and all of Andy’s toys.

Art Department

After reading the script, the Production Designer and Art Director decide how the film will look and feel. They make high-level decisions, and turn the details over to the Set Dresser.

The Set Dresser will then identify what props to use and what arrangement will best support the story.

In Andy’s case, we can see he is caught between his carefree days as a boy and his last days in high school before he goes off to college. Out of nostalgia, he holds on to his old favorite toys despite not playing with them anymore.

We, the audience, don’t need to see what’s in that tacklebox to know it’s just as unorganized as everything else in here. And that’s the power of environmental storytelling. Everything else in his room has already communicated that to us.

Case Study: What Horrors Await in Sid’s Room

To analyze environmental storytelling in the wild, we’re going to go back a few movies and look at the iconic scene from Pixar’s Toy Story (1995) where the antagonist, Sid, takes Buzz and Woody home to his room of tiny toy terror. If you don’t remember it, feel free to watch it again before continuing on.

I’m going to skip over the elements that show us Sid’s and his sister Hannah’s personalities (that’s more about visual storytelling and dialogue analysis) and focus just on the subtextual elements that make up the surroundings in this scene.

Enter Sid’s Room

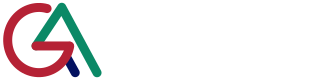

We learn a lot about Sid just by looking around his room. When he throws his ratty backpack on his bed, we see It doesn’t have sheets on it, barbed wire wraps the bedframe, and an “I ♥ EXPLOSIVES” bumper sticker adorns the wall.

As Sid prepares for “surgery” on his sister’s doll, Woody and Buzz take in their surroundings.

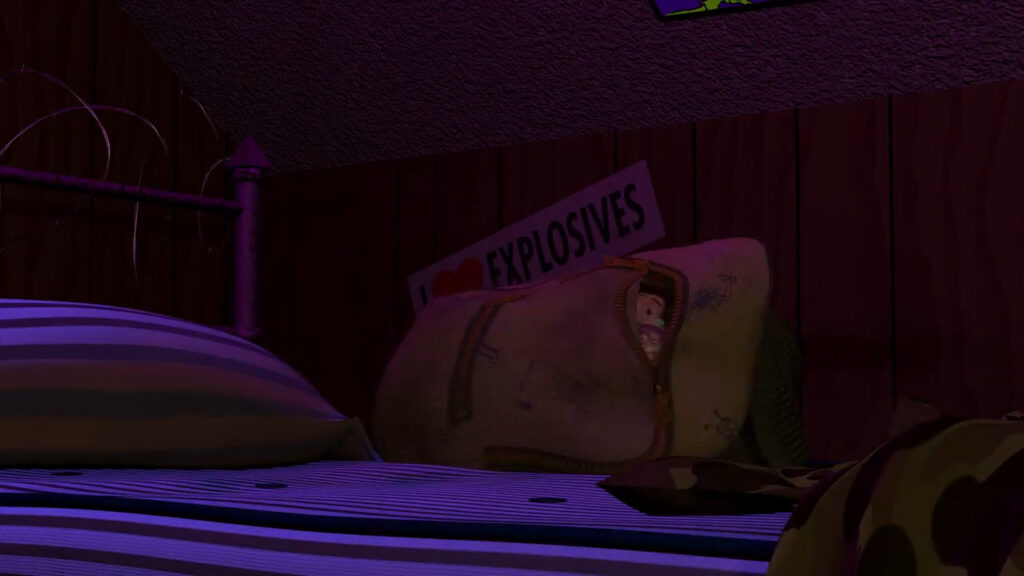

Like Andy and other kids, Sid’s room is a mess, but not in the same way. Andy’s room is cluttered with toys and his games. While Sid also has toys strewn about, notice how much garbage and trash he hasn’t thrown out. A single underpowered bulb lights the room. This room isn’t just messy, it’s unhealthy.

Side note, Sid is probably a victim of neglect, but I’ll leave that for another day.

To Woody, nothing is normal here.

Check out that poster for “Kill’n Paul Bunyon and His Blue Bull of Doom” where he wields a flamethrower. Classic Sid. Remember, great easter eggs don’t have to just tease your other works. Little details like this add a lot of flavor to the scene.

Once Sid leaves after completing his “surgery” on his sister’s doll, Woody encounters Sid’s other toys. He has broken and pieced all of them together using different items.

These toys are characters we will soon meet, but at this moment Woody doesn’t know they’re friends. Right now, they are just living manifestations of Sid’s unsettling domain, monsters in the night, and it terrifies him.

We didn’t need 5 minutes of backstory to explain why Sid is the way he is. Through a combination of his interactions with his sister, the room he lives in, and Woody’s reactions to this place, we have all the narrative we need to understand our heroes are in serious danger. That’s the power of environmental storytelling.

Tools and Techniques

To recap, consider these tips as you create your scenes:

- Show who your characters are by surrounding them with objects that have meaning to them

- Create the illusion of bigger worlds by hinting at details just out of reach

- Imply a deeper backstory than you have time to tell

- Include easter eggs for fans, but don’t go overboard

- Keep script descriptions simple, and let other departments do their job

Conclusion

As the first animation-only feature film, Pixar set the standard for a new storytelling medium. Toy Story became a classic for a lot of reasons, but the technical achievements aren’t why we still love it.

We don’t remember Toy Story for its amazing graphics. Pixar’s animation and rendering teams made significant improvements over the 15 years between Toy Story and Toy Story 3, but they would have never gotten a chance at those sequels if their first story sucked.

The story has to come first. People are willing to forgive some graphics issues if they can get lost in a good story. Use every tool, even the environment itself, to your advantage to give them that experience.